This is a reply to a comment from yesterday, as I wanted to add a couple of figures to explain my position better.

Thanks for continuing to participate, Otto.

My answer is that we will supply current demand load of electricity as we phase out coal rapidly by taking no options off the table in every country, and having a frank and open exchange of ideas about the overall cost/benefit of our electric power generation means. The discussion will be different in each country, but I will give you an example based on Australia to make my point.

But let’s not even talk about the means by which we will generate power, until we first talk about how we efficiently use the power we are generating now, and take whatever incentivised approaches we can to shift people and processes to more energy efficient operation. I am talking about boring old insulation, HVAC balancing, upgrades of lines, transformers, switch and “smart grid” technologies. As we begin that, we then should begin the design, siting and planning for the transitional power plants, and more speculative R&D on the long term power plants.

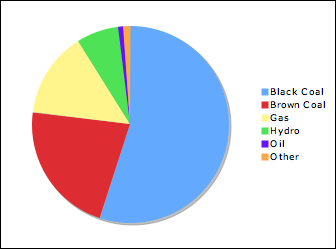

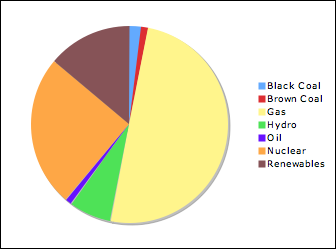

For example, I believe here in Australia, we should we should have the hard argument about going from 80% coal (the first figure) to something more like 44% gas (we have bucket loads of it), 25% nuclear, and a mix of other renewables (20%) over the next 10 years, as shown in the second figure. This is an aggressive target, and as I said should be combined with the even more aggressive push in energy efficiency.

2010:

2020:

That is why I think the major thrust of your argument is technically incorrect when you say there is only one thing that can do it, and you are far oversimplifying the argument if you say that all the other sources of energies combined cannot meet our current and future demand requirements. You should have some evidence to support this argument in the USA, if you conclude that only nuclear energy can address your situation.

And note the fatalism in your argument that “we cannot wait until the renewable technologies mature”. Mate, these technologies ARE mature. They work, they have achieved thermodynamic efficiencies that equal or exceed that of the internal combustion engine, and if I switched your place over to a couple of them, you would be surprised how reliable they would run your place, even when you need to keep the big screen tv in the fallout shelter, the weapons store and the underground water purification system running at the same time. However, if what you mean by mature is that they need to cost what the magic dirt does, then that isn’t going to happen. And why should it really? Coal is the false economy, and renewables technologies will never “mature” by falling in cost until there is guaranteed installed base to justify economy of scale in manufacturing, installation and maintenance. By believing only in one answer, you are participating in killing off the others.

While I don’t buy your argument about only nuclear being the solution, your solution could be partly correct. I think that we will have to operate with a significant potion of our electricity supplied by nuclear all over the world, wherever it makes the most appropriate sense. But only for about the lifetime of one plant, which might be closer to 20 years. Then we phase out nuclear and all the other bridging fuels that we can.

In the next five years worldwide, we need to be spending lots of time, money and resources in designing and implementing the energy efficiency improvements that we know already exist (anyone smell a big jobs stimulus package here?) right when we need it, and also possibly in doing some regulation of personal behaviour (maybe even some draconian regulation), but I will open up a heated argument on at a later date.